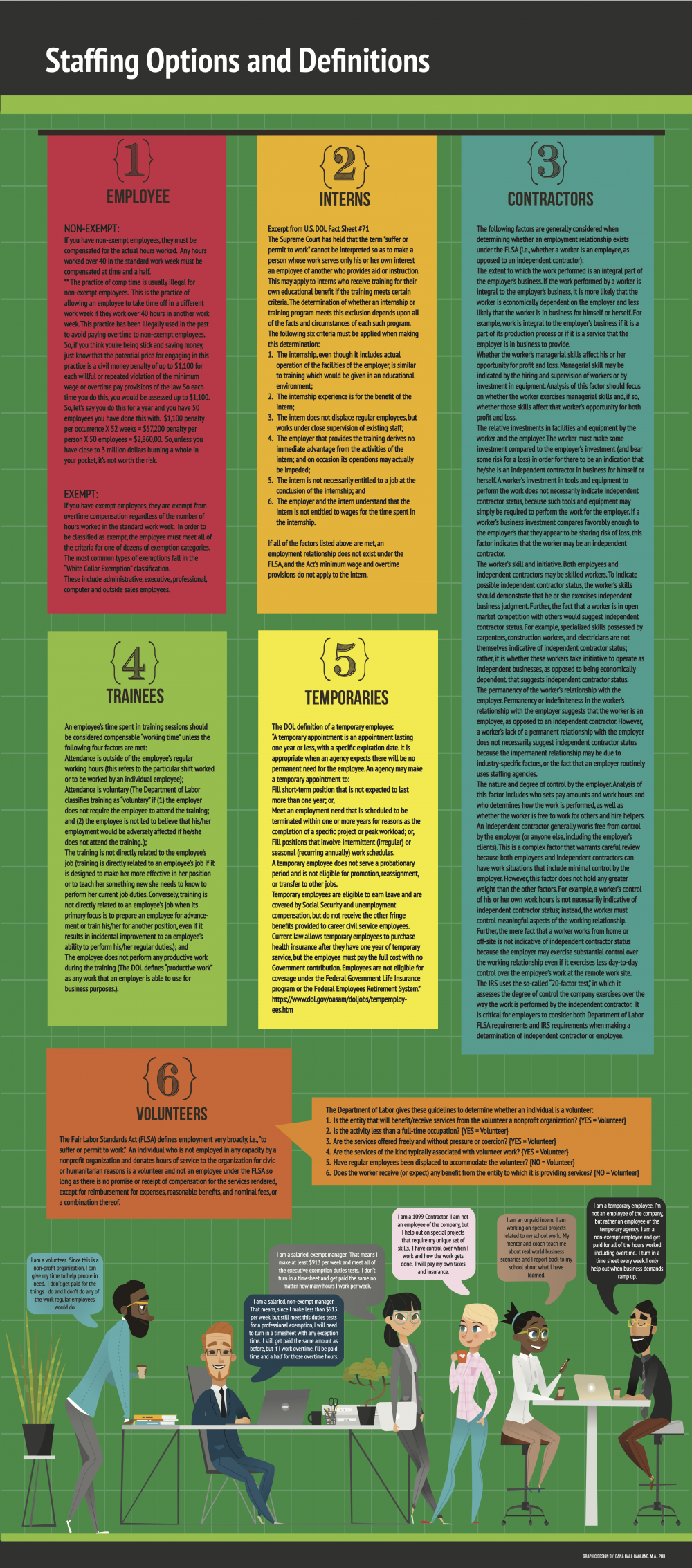

How to Boost Your Staffing Strategy [Infographic]

There are many different and creative ways to find the right mix of staffing strategies. The key to finding your mix begins with an understanding of what legal requirements apply for each type of person you may have performing work on your behalf. These are a few options, but there are certainly more currently being used and also those waiting to be discovered.

Companies with the greatest staffing success seem to also be experts in understanding what talent they need and when they need it. These definitions and clarifications on legal requirements for staffing will help you begin to define or refine your current and future needs.

NON-EXEMPT EMPLOYEES

If you have non-exempt employees, they must be compensated for the actual hours worked. Any hours worked over 40 in the standard workweek must be compensated at time and a half.

The practice of comp time is usually illegal for non-exempt employees. This is the practice of allowing an employee to take time off in a different work week if they work over 40 hours in another work week. This practice has been illegally used in the past to avoid paying overtime to non-exempt employees.

So if you have been using this or are using this method, just know that the potential price for engaging in this practice is a civil money penalty of up to $1,100 for each willful or repeated violation of the minimum wage or overtime pay provisions of the law. So each time you do this, you would be assessed up to $1,100.

Let’s say you do this for a year and you have 50 employees you have done this with. $1,100 penalty per occurrence X 52 weeks = $57,200 penalty per person X 50 employees = $2,860,000. Unless you have close to 3 million dollars burning a whole in your pocket, it’s not worth the risk.

EXEMPT EMPLOYEES

If you have exempt employees, they are exempt from overtime compensation regardless of the number of hours worked in the standard work week. In order to be classified as exempt, the employee must meet all of the criteria for one of dozens of exemption categories.

The most common types of exemptions fall in the “White Collar Exemption” classification. These include administrative, executive, professional, computer and outside sales employees. Check out this guide by the U.S. Department of Labor if you are not sure about exempt status for your employee.

VOLUNTEERS

The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) defines employment very broadly (i.e., “to suffer or permit to work”). An individual who is not employed in any capacity by a nonprofit organization and donates hours of service to the organization for civic or humanitarian reasons is a volunteer and not an employee under the FLSA so long as there is no promise or receipt of compensation for the services rendered, except for reimbursement for expenses, reasonable benefits, and nominal fees, or a combination thereof.

The Department of Labor gives these guidelines to help you determine whether an individual is a volunteer:

- Is the entity that will benefit/receive services from the volunteer a nonprofit organization? {YES=Volunteer}

- Is the activity less than a full-time occupation? {YES=Volunteer}

- Are the services offered freely and without pressure or coercion? {YES = Volunteer}

- Are the services of the kind typically associated with volunteer work? {YES = Volunteer}

- Have regular employees been displaced to accommodate the volunteer? {NO = Volunteer}

- Does the worker receive (or expect) any benefit from the entity to which it is providing services? {NO = Volunteer}

All six criteria must be met.

INTERNS

Excerpt from U.S. DOL Fact Sheet #71:

“The Supreme Court has held that the term ‘suffer or permit to work’ cannot be interpreted so as to make a person whose work serves only his or her own interest an employee of another who provides aid or instruction. This may apply to interns who receive training for their own educational benefit if the training meets certain criteria. The determination of whether an internship or training program meets this exclusion depends upon all of the facts and circumstances of each such program.

The following six criteria must be applied when making this determination:

- The internship, even though it includes actual operation of the facilities of the employer, is similar to training which would be given in an educational environment;

- The internship experience is for the benefit of the intern;

- The intern does not displace regular employees, but works under close supervision of existing staff;

- The employer that provides the training derives no immediate advantage from the activities of the intern; and on occasion its operations may actually be impeded;

- The intern is not necessarily entitled to a job at the conclusion of the internship; and

- The employer and the intern understand that the intern is not entitled to wages for the time spent in the internship.

If all of the factors listed above are met, an employment relationship does not exist under the FLSA, and the Act’s minimum wage and overtime provisions do not apply to the intern.”

TRAINEES

An employee’s time spent in training sessions should be considered compensable “working time” unless the following four factors are met:

- Attendance is outside of the employee’s regular working hours (this refers to the particular shift worked or to be worked by an individual employee);

- Attendance is voluntary (The Department of Labor classifies training as “voluntary” if (1) the employer does not require the employee to attend the training; and (2) the employee is not led to believe that his/her employment would be adversely affected if he/she does not attend the training.);

- The training is not directly related to the employee’s job (training is directly related to an employee’s job if it is designed to make him/her more effective in his/her position or to teach him/her something new he/she needs to know to perform his/her current job duties. Conversely, training is not directly related to an employee’s job when its primary focus is to prepare an employee for advancement or train him/her for another position, even if it results in incidental improvement to an employee’s ability to perform his/her regular duties.); and

- The employee does not perform any productive work during the training (The DOL defines “productive work” as any work that an employer is able to use for business purposes).

INDEPENDENT CONTRACTORS

The following factors are generally considered when determining whether an employment relationship exists under the FLSA (i.e., whether a worker is an employee, as opposed to an independent contractor):

- The extent to which the work performed is an integral part of the employer’s business. If the work performed by a worker is integral to the employer’s business, it is more likely that the worker is economically dependent on the employer and less likely that the worker is in business for himself or herself. For example, work is integral to the employer’s business if it is a part of its production process or if it is a service that the employer is in business to provide.

- Whether the worker’s managerial skills affect his or her opportunity for profit and loss. Managerial skill may be indicated by the hiring and supervision of workers or by investment in equipment. Analysis of this factor should focus on whether the worker exercises managerial skills and, if so, whether those skills affect that worker’s opportunity for both profit and loss.

- The relative investments in facilities and equipment by the worker and the employer. The worker must make some investment compared to the employer’s investment (and bear some risk for a loss) in order for there to be an indication that he/she is an independent contractor in business for himself or herself. A worker’s investment in tools and equipment to perform the work does not necessarily indicate independent contractor status, because such tools and equipment may simply be required to perform the work for the employer. If a worker’s business investment compares favorably enough to the employer’s that they appear to be sharing risk of loss, this factor indicates that the worker may be an independent contractor.

- The worker’s skill and initiative. Both employees and independent contractors may be skilled workers. To indicate possible independent contractor status, the worker’s skills should demonstrate that he or she exercises independent business judgment. Further, the fact that a worker is in open market competition with others would suggest independent contractor status. For example, specialized skills possessed by carpenters, construction workers, and electricians are not themselves indicative of independent contractor status; rather, it is whether these workers take initiative to operate as independent businesses, as opposed to being economically dependent, that suggests independent contractor status.

- The permanency of the worker’s relationship with the employer. Permanency or indefiniteness in the worker’s relationship with the employer suggests that the worker is an employee, as opposed to an independent contractor. However, a worker’s lack of a permanent relationship with the employer does not necessarily suggest independent contractor status because the impermanent relationship may be due to industry-specific factors, or the fact that an employer routinely uses staffing agencies.

- The nature and degree of control by the employer. Analysis of this factor includes who sets pay amounts and work hours and who determines how the work is performed, as well as whether the worker is free to work for others and hire helpers. An independent contractor generally works free from control by the employer (or anyone else, including the employer’s clients). This is a complex factor that warrants careful review because both employees and independent contractors can have work situations that include minimal control by the employer. However, this factor does not hold any greater weight than the other factors. For example, a worker’s control of his or her own work hours is not necessarily indicative of independent contractor status; instead, the worker must control meaningful aspects of the working relationship. Further, the mere fact that a worker works from home or offsite is not indicative of independent contractor status because the employer may exercise substantial control over the working relationship even if it exercises less day-to-day control over the employee’s work at the remote worksite.

The IRS uses the so-called “20-factor test,” in which it assesses the degree of control the company exercises over the way the work is performed by the independent contractor. It is critical for employers to consider both Department of Labor FLSA requirements and IRS requirements when making a determination of independent contractor or employee.

TEMPORARY EMPLOYEES

The DOL definition of a temporary employee is:

“A temporary appointment is an appointment lasting one year or less, with a specific expiration date. It is appropriate when an agency expects there will be no permanent need for the employee. An agency may make a temporary appointment to:

- Fill short-term position that is not expected to last more than one year; or,

- Meet an employment need that is scheduled to be terminated within one or more years for reasons as the completion of a specific project or peak workload; or,

- Fill positions that involve intermittent (irregular) or seasonal (recurring annually) work schedules.

- A temporary employee does not serve a probationary period and is not eligible for promotion, reassignment, or transfer to other jobs.

Temporary employees are eligible to earn leave and are covered by Social Security and unemployment compensation, but do not receive the other fringe benefits provided to career civil service employees. Current law allows temporary employees to purchase health insurance after they have one year of temporary service, but the employee must pay the full cost with no Government contribution.

Employees are not eligible for coverage under the Federal Government Life Insurance program or the Federal Employees Retirement System.”

Once again, these are basic guides and staffing concepts. None of the above is intended to be legal advice. You should contact legal counsel if you have concerns about the classification of your workers.